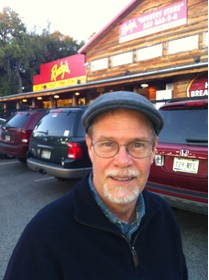

We are pleased to welcome Keith McCleary to Writers on Craft this month. Keith McCleary is a writer and graphic designer from New York, currently living in Southern California. He is the author of several graphic novels, as well as assorted prose, poetry, and digital media. Keith holds an MFA in Creative Writing from UC San Diego, and a BFA in Film from NYU. He teaches and writes about comics, composition, and multimedia.

We are pleased to welcome Keith McCleary to Writers on Craft this month. Keith McCleary is a writer and graphic designer from New York, currently living in Southern California. He is the author of several graphic novels, as well as assorted prose, poetry, and digital media. Keith holds an MFA in Creative Writing from UC San Diego, and a BFA in Film from NYU. He teaches and writes about comics, composition, and multimedia.

What do you read when you despair at the state of either your work or a particularly difficult manuscript in progress—any “go to” texts?

I don’t know if I despair about the things other writers and artists despair about—I don’t usually have a problem with generating new work, or with the state of the work itself. Not that I think everything I do is perfect, but I’m usually fairly confident that I can get what I’m writing into decent shape with enough elbow grease. My despair is rooted squarely in getting the work out there—I’ve never been great about self-promotion, and doing it makes me feel a little sick. In that sense I always feel like I’m falling short of the expectations I place on myself. That’s despair for me.

That was a long preamble, and I don’t know if my specific anxieties color the ways in which I take textual refuge. I ultimately feel like there are still two answers to the question of “go to” texts: the kinds of texts I go to in order to center myself or be inspired, and the kind of texts I go to for comfort and decompression.

I suppose the work that centers me and makes me feel less awful about the demise of the world might be comics by Peter Milligan and Brendan McCarthy—together or individually, pretty much anything they’ve done. Paul Pope’s 100%. Farel Dalrymple’s work, and Jaime Hernandez’s Love and Rockets stories. Stephen Murphy and Michael Zulli’s The Puma Blues. Tank Girl. Scott Pilgrim. Grant Morrison sometimes, when he’s really on, although a lot of his work is so self-congratulatory it makes me hate art.

Comfort food reading is pretty much any X-Men comic from Grant Morrison’s run forward, and any Batman comic from Kelley Jones’ run backward.

Warren Ellis’ Transmetropolitan and Neil Gaiman’s Sandman, and everything Alan Moore has ever written, fit in both categories—both centering and comfort food.

Since you’re a visual artist as well, working with comics and graphic texts, are you more drawn to visual media as inspiration? Which websites or forums are particularly inspiring for those in your field/s?

Seeing as I only listed comics for the first question, I think the obvious answer is that comics are where my influences come from. Films and prose also fill in some of the blanks—I feel like I read a book or so each year, and see a film or so each year, that gets added to my personal canon in a meaningful way.

I think that visual media and music is what inspires me. Prose is more instructive to me. I’ll read a book and think about new things I can try with voice and language and structure. I get really microcosmic in order to figure out how a writer is creating an effect, or why something they’re trying to do isn’t working. In either case, I end up adding more tools to my toolbox. But when I’m writing, I’m probably just thinking something like “This should feel like Blade Runner meets Fever Ray.”

I’m not sure that I get inspired by specific websites. Like most humans, I live on Facebook and Tumblr, and I think that following people whose work I like, and being able to see those people produce and just be human on a daily basis, is the most useful thing for me.

If you could give just one piece of advice to emerging authors or artists about editing or storyboarding that has served you well, what would it be?

If you could give just one piece of advice to emerging authors or artists about editing or storyboarding that has served you well, what would it be?

Hm. I work with a lot of new writers both in my teaching and editing, and I think the trend I see most often is that people treat writing like editing, and editing like writing. A lot of people get frozen at the starting line, or write mud-slow, because they’re terrified that every word they’re going to write might be the wrong one. I see new writers attempting to draft an entire work in their minds before they’ve typed a line, and spending too much time fixing the sentences on page one when they should be halfway through writing page five.

Conversely, when the draft is finished, these same people stubbornly refuse to change a word. They think that “editing” means grammar and typos, instead of deeply taking stock of what it is they’ve created, and helping that work be its best self. The work’s gotta be perfect out of the gate, and if someone suggests it’s not, the walls go up.

You’ve got to let writing be writing, and editing be editing. That’s rule one. When you’re writing, you need to trust that everything you’re putting down is genius. Trust yourself completely. Be embarrassingly self-indulgent. When you’re editing, then the claws come out.

Today I had a student who asked me how to start writing a novel. He said his biggest problem was that he didn’t know what the moral of his story should be. Like, a moral? Who cares? Write something down. Get it started. How can you know what you’re trying to say until you try saying something?

As you progress with multiple projects, has your perception of what you “do” with your work changed as you have continued to write and draw? Are you impacted by the external world in different ways?

I had an artistic crisis about ten years ago when I had to own up to the fact that I was a straight white guy telling straight white guy stories. I was living in New York City at the time, and I was really aware of how much I was reinforcing stereotypes about writerly subjectivity just by being alive. I didn’t want to try and appropriate a wider perspective in some way that felt false, but I also couldn’t continue what I was doing.

I had an artistic crisis about ten years ago when I had to own up to the fact that I was a straight white guy telling straight white guy stories. I was living in New York City at the time, and I was really aware of how much I was reinforcing stereotypes about writerly subjectivity just by being alive. I didn’t want to try and appropriate a wider perspective in some way that felt false, but I also couldn’t continue what I was doing.

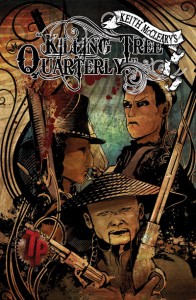

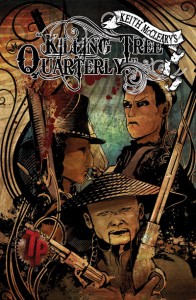

I know that my first comic, Killing Tree Quarterly, came out of that frustration—it’s this politically incorrect western about multicultural assassins that, for me, felt both really taboo and also historically accurate in a lot of ways. That project opened me up quite a bit, and got me thinking about how I could push my limits while still being honest with who I was as a writer.

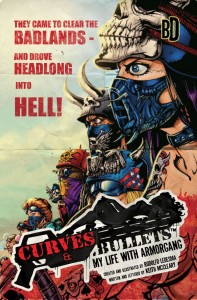

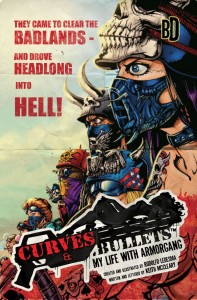

I suppose there’s still sort of a political soapbox festering in the work I do these days, and maybe I’ve gotten more comfortable having my politics filter into my writing. The comic I write now is called Curves & Bullets, and it’s sort of Tank Girl meets GI Joe. I knew when I teamed up with the artist, Rolo Ledesma, that all he wanted to do was draw scantily-clad women on motorcycles. I remember thinking, “My day job is being a grad student and teaching writing to 18-year-olds—this is going to be a lot for me to reconcile.”

I went back to Larry Hama’s old GI Joe comics from the 1980’s, and was reminded that the main thing those stories focused on was camaraderie and kicking ass, with no mention of the fact that the characters were a bunch of sweaty, ripped, half-naked dudes. So I wrote Curves & Bullets with the same basic guidelines. After our first issue came out, I immediately got responses that it was “weirdly feminist.” And my girlfriend points out that it’s one of the few action comics she can read that passes the Bechdel test. So, you know, small victories.

I guess the short answer is that I’m a genre writer with personal politics that don’t always jive with the tropes of the genres in which I work. I try to just let those two sides of myself disrupt each other as naturally as I can.

What do you feel is the purpose of literature or art? Feel free to answer separately.

I really don’t feel there’s a purpose for either. It’s like wood. Wood has no inherent purpose except to the tree. Saying that wood’s purpose is to be a chair, or a house—that feels sort of imperialistic. I know the implication here is for me to explain the purpose of my literature or art, but even that’s too much for me.

I do think it’s important to understand a particular project’s purpose, and to evaluate the worth of that purpose. But that’s case-by-case, and involves making sure you understand and abide by the rules of the thing you’re making, as you make it. It’s not about the purpose of literature or art as a grand gesture.

Here’s what I think: make the thing. Worry about what it means later. If you try to assign purpose to an entire medium, that’s editing. Editing something that isn’t done yet, that won’t be done until we’re done. See rule one.

You’ve been a design assistant, a proofreader, a video editor and graphic designer, a writing coach—how does having worn so many hats influence your selection of new projects?

I suppose sometimes I take on a project just because I want to see if I can do it. But more often, I take on projects that I think will be easy and straightforward, and then they’re not. And then I have to learn how to do something new in order to get them done.

That’s the cranky answer. I guess the real answer is that each new thing I learn to do helps me do everything else better. Two summers ago, Grant Leuning suggested I start running a game of Shadowrun for a group of our friends. Designing game scenarios instantly began influencing my writing, and managing a group of peers through those scenarios both drew upon and impacted my teaching. The more stuff you know how to do, the more stuff you know how to do.

Till you do too many things, and then you get cranky. Just ask anyone who’s ever collaborated with me.

What do you dream of, when you dream big, for where you’d like to be in your art or process in the next ten years?

Main thing, above all other things—I’d like to get over my hangups about submitting and have some work out on a large press. I’d like to have an agent—I hear they’re useful. I have a rather unwieldy 300-page “word hoard” kind of manuscript that I’d like to devote a summer to. Sophia Starmack and I wrote a teleplay for CCLaP a few years ago called The Gothickers, and we have at least a hundred pages of more Gothickers material that we need a winter abroad in order to finish.

Someday I would like to have an ongoing comic series with a big publisher. Someday I would like to write X-Men.

I also just want to get really good at Netrunner.

As a human being, what is the best advice you have to offer?

I feel like what I’m supposed to say here is that it’s important to love, to listen, to be. Or something. Something that would look good in an inspirational font with a beach scene behind it. But my preferred response to this question is Gary Oldman’s, when asked about his personal motto: “Fuck ‘em.”

I guess I would say, you know, three things: Get enough sleep. Don’t be afraid to be critical. Fuck ‘em.

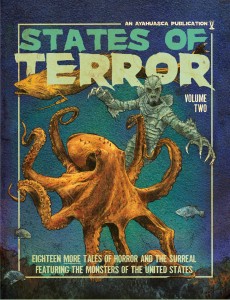

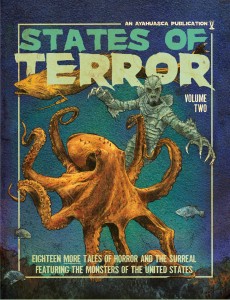

With Matt E. Lewis, you’ve been engaged with editing a three volume project called States of Terror that pairs artists and authors to create a wonderful series of horror stories with illustrations. That’s an exciting multi-volume project. Can you speak to that?

Matt publishes a zine called The Radvocate, and he emailed me about a year ago when he was between issues. He said he was kicking around the ideas for a Halloween zine that would focus on monsters from each of the fifty states, and he wanted to know if I had any interest in collaborating. I kind of had an image right away for how I wanted it to look and feel, so I said yes. I’d worked with our art director, Adam Miller, on a variety of comic book projects for years, so I asked him if he knew three of four artists who might be willing to do illustrations for 20 or so stories. Adam said, “Well, how about 20 artists then?” We ended up with an artist and writer for each state monster, and our first volume covered 18 states.

I remember that about 72 hours after Matt sent me that first email, we had the title, the aesthetic, all the monsters, and probably 95% of the writers and artists. I crunched the numbers and realized that our “zine” was going to end up being a 200-page book, and we’d set ourselves a goal of getting the whole thing written, edited, assembled, and printed in a month. I think we ended up taking two months with it, but it was really nuts. The second volume just came out last month, and we got a ton of amazing people to contribute. It also took much longer to make, and was probably even more nuts.

The series has opened a lot of doors for us. We’ve gotten to know all these accomplished and talented people in a way that’s felt natural and fun, and I like that the project balances all the worlds I straddle personally—comics and fiction, literary and genre writing, graphic design and prose editing. To me the project feels so traditional in a lot of ways—the entire thing is modeled after old Creepy and Eerie magazines—but people seem to freak out at its hybridity, at all the things it’s doing. That’s kind of funny to me, but also really validating.

I’m really drawn to your comic Top of the Heap, available on your website, about a circus train crashing and the animals foraging for survival. One of my favorite things about it is both how the drawings themselves are so evocative and also how the text functions with both power and density (readers of this interview are invited to go read it). “The ringmaster and the acrobats served as food the first three days,” is the text on the first page depicting a crash, for example, spread across the artwork, moving along a diagonal in a visually appealing way. It almost seems each page is its own micro fiction entry, though they work together. The next page reads only, “The clowns were next.” When you pair image and text, is one or the other always primary, or at least in your first inclination?

I’m really drawn to your comic Top of the Heap, available on your website, about a circus train crashing and the animals foraging for survival. One of my favorite things about it is both how the drawings themselves are so evocative and also how the text functions with both power and density (readers of this interview are invited to go read it). “The ringmaster and the acrobats served as food the first three days,” is the text on the first page depicting a crash, for example, spread across the artwork, moving along a diagonal in a visually appealing way. It almost seems each page is its own micro fiction entry, though they work together. The next page reads only, “The clowns were next.” When you pair image and text, is one or the other always primary, or at least in your first inclination?

Top of the Heap had a pretty strict set of self-imposed rules—I felt that each page had to require both text and image to make sense, and that the reader wouldn’t get the story unless they interacted with both. This comes from my experience with comics and picture books. It’s always easy to tell when you’re reading a comic that was created script-first—there’s way too much dialogue, and panel after panel of talking heads. It’s like a low-budget TV show on a single set. Comics that are planned visually, and then use text as support, almost always offer a more immersive experience even if the story is somewhat simple.

I think the same thing holds true for picture books. My mother taught children’s literature for most of her career, so I grew up with a lot of picture books around the house. I always felt a little let down by books that would have blocks of text on one page, with an illustration opposite. It seemed like a lost opportunity.

Alan Moore has written quite a bit about the uniqueness of the interplay between text and images in comics, and all the things that comics can do to a reader that no other form can do. When I make comics, I’m interested in exploiting the medium’s strengths in whatever ways I can.

With this comic, you tell a big story with few words. Can you tell us how the vivid artwork and structure of the narrative was conceived?

Both Top of the Heap and Killing Tree Quarterly were illustrated using a combination of Photoshop and Poser, which is consumer-grade 3D software that, as far as I can tell, is mostly used in the creation of animated porn. I learned about Poser back in 2006 at the first New York Comic Con, where they’d set up a booth and were running demos. I thought the renders looked kind of junky, actually, but I figured I could use my graphic design chops to clean them up. I’d been looking for a way to make comics on my own without having to rely on my shaky drawing hand, so it was a real boon for me.

Both Top of the Heap and Killing Tree Quarterly were illustrated using a combination of Photoshop and Poser, which is consumer-grade 3D software that, as far as I can tell, is mostly used in the creation of animated porn. I learned about Poser back in 2006 at the first New York Comic Con, where they’d set up a booth and were running demos. I thought the renders looked kind of junky, actually, but I figured I could use my graphic design chops to clean them up. I’d been looking for a way to make comics on my own without having to rely on my shaky drawing hand, so it was a real boon for me.

On a technical level, the way my process worked was that I would design the characters and make setpieces in 3D, set the lights and the camera angles, and then render still images to make my panels. The backgrounds were usually some kind of photomontage, run through a bunch of filters (and sometimes even run through Poser as two-dimensional objects) in order to make the whole thing more seamless. My assembly was all in Photoshop, and I think some of those pages ended up with over 100 layers.

In terms of conceptualizing the project, I started with a three-page prose story, as I mentioned. I originally had the idea that each page would have multiple panels like a traditional comic, but the renders were so complicated and labor intensive that doing full-page images ended up making more sense. Then it was just a LOT of storyboarding, stripping the story down to its most basic elements, the fewest number of beats I could while still keeping the text minimal. Not including pre-planning, I think making the book took about six months. I remember writing down “Show, Don’t Tell” on all of my notes. How could I make an entire story with zero dialogue and zero exposition? Show, don’t tell. Show, don’t tell. I still look back on it and see sentences that feel too long.

You run The New Comics, an ongoing interview series, on Entropy. How do you find the time to do all the things you do? Is it service to the comic community to support the work of other artists?

I don’t think I manage my time as well as I could. It’s only when I look backward that it feels like I’ve done a lot of stuff. Any time I’m focused on one project, that means three others are getting ignored. I was having a conversation with Nick Francis Potter when I interviewed him, and we agreed that the main way we knew of to get multiple projects done at once is to use them against each other—when you’re procrastinating on one thing, use that time to do another thing. Getting two projects done at once is somehow easier than focusing on one.

In terms of the Entropy gig, I’d been wanting to work with that group for a long time. I have a lot of respect for Janice Lee and Michael Seidlinger—talk about workhorses. Those two aren’t even human. When Janice put out a call that she was looking for someone who could curate comic content for them, I knew that was something I could do better than anyone else. I think that was literally my pitch: “I know what you want, and I know you will not find anyone else who knows how to do it.” Being able to bridge indie lit and comics, that’s pretty tricky, but it’s right in the middle of my particular sandbox.

I do like to support the work of people I like—I don’t know that I consciously think about the ‘community,’ per se, but I’m interested in spotlighting people who are good, who might be like me in that they’re still in the process of figuring out how to get their creative machine up and running. Helping to make that happen, or to talk to people about how they’re tackling the problem, is really cathartic for me. It’s made my own insecurities less insurmountable. It’s made me feel less alone. I just wish I had the time to do more interviews, but I’m happy each time we finish one and get the work out there.

Regarding fiction, you have a blog called Gchatus where flash fiction is the primary medium. There are some beautiful pieces there. I particularly like the piece called “On a Beach Outside: Fanfiction” where the text reads, “We forget that there are a thousand universes and we are lucky to live in this one. We doubt that this means we are allowed to want for larger things, to hunger for wider spaces. Our luck does not exclude the possibility for wanting more.” The depth of the work is clear. But you also have a novel you’re shopping and a graphic novel, can you speak to moving between short work and long work in prose? How your process works?

Regarding fiction, you have a blog called Gchatus where flash fiction is the primary medium. There are some beautiful pieces there. I particularly like the piece called “On a Beach Outside: Fanfiction” where the text reads, “We forget that there are a thousand universes and we are lucky to live in this one. We doubt that this means we are allowed to want for larger things, to hunger for wider spaces. Our luck does not exclude the possibility for wanting more.” The depth of the work is clear. But you also have a novel you’re shopping and a graphic novel, can you speak to moving between short work and long work in prose? How your process works?

Gchatus started when I was at a particularly low point in my writing—I think I was stop-starting on a novel, and otherwise didn’t have a lot going on. I was envious of my artist friends who were drawing every day, especially because I would see them post their warm-up drawings on social media each morning. It seemed like a nice way to break up the isolation of making new material, and to build a bit of a fanbase at the same time. I started writing these microfictions—maybe 80 words max—in my gchat status box, and when I had enough of them I began a Tumblr. I did one every day, and pretty soon my longform writing started getting better. I just felt so much more well-oiled.

When I was writing the rough draft of the novel you mentioned, I was working a desk job where I knew no one would ask me to do anything before 11am, even though I had to be at my desk at 9. So each morning I would come in, brew some tea, write a gchatus, and then do 1000 words on my manuscript. Five days a week, weekends off.

I don’t use the blog as regularly now, but I think writing short fiction has REALLY helped my long fiction. Minimalism is the key to everything—even if I’m writing longform, I’m jumping from topic to topic, trying to make a collage of the best bits. It’s just that I’m building bigger and bigger collages.

Other than that, my process is really straightforward. I write. I force myself to write. I force my fingers to move. I have a little outline for a new project I’m working on, but it’s only about a page of notes—when Sophia Starmack and I started writing together, we decided we would aim for a 60 thousand word book by writing 12 chapters, 5 partitions per chapter. 60 little parts, a thousand words each. I still use the same formula. It’s a completely arbitrary formula, and you’ve got to be willing to let yourself tangent from it so that things stay fresh. The only purpose of the formula is to help you generate a draft, and by extension the only purpose of the draft is to give you something to revise. Revision is where the actual work lies. Until then, you’ve just got to do whatever it takes to make yourself into a word-churning machine.

When I sit down to write, I tend to just put on pop songs on repeat and zone out, then check my word count after I run out of steam. If the writing is getting boring, I turn the scene around until I can see another way in. I remember once I was riding the L train from Manhattan to Brooklyn, and there was a guy across from me with a Rubiks Cube. He kept tossing the cube in his hand, and with every few tosses the panels would have a new pattern on them—checkerboard, flat colors, other things. When I’m writing and hit a wall, I stop and I think about what I’m writing like that cube. I throw it around until I can see something else to do with it.

What’s in the immediate pipeline for your readers next? And what are you working on now? Give us a sneak peek.

What’s in the immediate pipeline for your readers next? And what are you working on now? Give us a sneak peek.

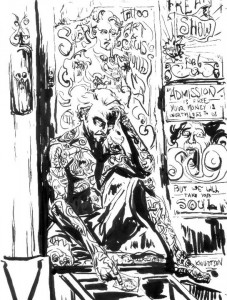

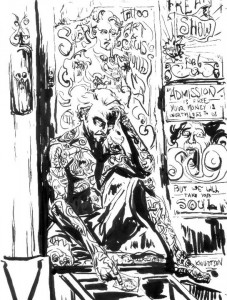

The novel I’m shopping is called CIRCUS+THE SKIN, and it’s about a tattooed man at a circus who’s also a war veteran, and who starts losing his grip on reality after his circus is wiped out by a bad storm while en route through the Midwest. It’s got some elements of noir and horror and western gothic in it, and right now I feel pretty good about it. I’ve had a bit of it published in Weave with some amazing art from Ken Knudtsen, and more of it is due to appear in New Dead Families next year.

Matt and Adam and I are going to start production on States of Terror Vol 3 just as soon as we’re properly recovered from Vol 2, and Rolo has started pestering me for thumbnails so we can start the next issue of Curves & Bullets.

Other than that, I’m in the middle of hardcore NaNoWriMo’ing with some other San Diego writers. I’ve always sort of poo-pooed NNWM in the past, but I’m getting a lot out of it. I’m already about halfway through a new manuscript. It’s this big cyberpunk thing about a guy who’s addicted to reprogramming his personality through a hard drive in his head. I’m trying not to read back on it too much, but I wrote this paragraph yesterday and liked it, so I’ll just add it here:

“You might think that there is something profane in the way that we watch each other, the way each moment is not a true thing but simply an instant to be monitored and recorded, catalogued and framed. To this I ask you, have you engaged in the glory of a collective? To you know what it is to bring an Indian Elephant made of wood to life? How is it not that we are working together toward constant theater? How is it that this unliving is not in fact us at our most alive?”

Writers on Craft is hosted by Heather Fowler, who cares about writing. She does a lot of it. Visit her profile on Fictionaut or see here for more: www.heatherfowlerwrites.com.

When asked to serve as Editor’s Eye for a second time. I felt as flattered and unworthy as the first time I was asked. In the over three years I’ve been posting and commenting on Fictionaut I’ve found something to admire in nearly every piece that comes up in the Recent Stories. I remain in awe of the overall talent, convinced I’m the only writer here without a MFA or other pedigree signifying literary expertise.

When asked to serve as Editor’s Eye for a second time. I felt as flattered and unworthy as the first time I was asked. In the over three years I’ve been posting and commenting on Fictionaut I’ve found something to admire in nearly every piece that comes up in the Recent Stories. I remain in awe of the overall talent, convinced I’m the only writer here without a MFA or other pedigree signifying literary expertise.

If you could give just one piece of advice to emerging authors or artists about editing or storyboarding that has served you well, what would it be?

If you could give just one piece of advice to emerging authors or artists about editing or storyboarding that has served you well, what would it be? I had an artistic crisis about ten years ago when I had to own up to the fact that I was a straight white guy telling straight white guy stories. I was living in New York City at the time, and I was really aware of how much I was reinforcing stereotypes about writerly subjectivity just by being alive. I didn’t want to try and appropriate a wider perspective in some way that felt false, but I also couldn’t continue what I was doing.

I had an artistic crisis about ten years ago when I had to own up to the fact that I was a straight white guy telling straight white guy stories. I was living in New York City at the time, and I was really aware of how much I was reinforcing stereotypes about writerly subjectivity just by being alive. I didn’t want to try and appropriate a wider perspective in some way that felt false, but I also couldn’t continue what I was doing. I’m really drawn to your comic

I’m really drawn to your comic  Both Top of the Heap and Killing Tree Quarterly were illustrated using a combination of Photoshop and Poser, which is consumer-grade 3D software that, as far as I can tell, is mostly used in the creation of animated porn. I learned about Poser back in 2006 at the first New York Comic Con, where they’d set up a booth and were running demos. I thought the renders looked kind of junky, actually, but I figured I could use my graphic design chops to clean them up. I’d been looking for a way to make comics on my own without having to rely on my shaky drawing hand, so it was a real boon for me.

Both Top of the Heap and Killing Tree Quarterly were illustrated using a combination of Photoshop and Poser, which is consumer-grade 3D software that, as far as I can tell, is mostly used in the creation of animated porn. I learned about Poser back in 2006 at the first New York Comic Con, where they’d set up a booth and were running demos. I thought the renders looked kind of junky, actually, but I figured I could use my graphic design chops to clean them up. I’d been looking for a way to make comics on my own without having to rely on my shaky drawing hand, so it was a real boon for me. Regarding fiction, you have a blog called

Regarding fiction, you have a blog called  What’s in the immediate pipeline for your readers next? And what are you working on now? Give us a sneak peek.

What’s in the immediate pipeline for your readers next? And what are you working on now? Give us a sneak peek.