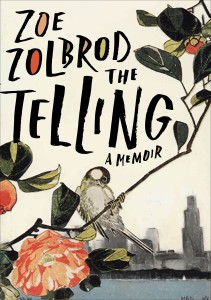

We are pleased to welcome Zoe Zolbrod to this month’s Writers on Craft. Zoe Zolbrod is the author of the memoir The Telling (Curbside Splendor, 2016) and the novel Currency (Other Voices Books, 2010), which was a Friends of American Writers prize finalist. Her essays have appeared in Salon, Stir Journal, The Weeklings, The Manifest Station, The Nervous Breakdown, The Chicago Reader, and The Rumpus, where she is the Sunday co-editor. She’s had numerous short stories and interviews with authors published, too. Born in western Pennsylvania, Zolbrod now lives in Evanston, IL, with her husband and two children.

We are pleased to welcome Zoe Zolbrod to this month’s Writers on Craft. Zoe Zolbrod is the author of the memoir The Telling (Curbside Splendor, 2016) and the novel Currency (Other Voices Books, 2010), which was a Friends of American Writers prize finalist. Her essays have appeared in Salon, Stir Journal, The Weeklings, The Manifest Station, The Nervous Breakdown, The Chicago Reader, and The Rumpus, where she is the Sunday co-editor. She’s had numerous short stories and interviews with authors published, too. Born in western Pennsylvania, Zolbrod now lives in Evanston, IL, with her husband and two children.

You’ve done a lot of interesting work with essays and creative non-fiction as well as novel writing. Is there any difference in your approach to writing different genres in terms of writing process and the speed of generating work when you approach creative non-fiction as opposed to fiction? Do you find you enjoy different genres more or less at different times in your life?

My novel Currency is set in Thailand, where I spent some time, and my memoir involves not only my personal experience but also a look at the broader topic childhood sexual abuse and pedophilia, so my writing process for both books involved a look back at journals and a fair amount of research. I was a little more efficient in writing the memoir, at least in the sense that fewer pages were left on the cutting room floor by the end. But any time I might have saved in limiting my material to scenes from my own life was balanced out by the psychological piece of dealing some pretty heavy stuff from my past. After trying so hard to be accurate and fair in the memoir, I look forward to getting back to fiction and letting my imagination run wild. On the flip side, I bet I’ll miss the thing that I like most about nonfiction: Speaking directly to issues of the day that preoccupy me.

If you could give just one piece of advice to emerging authors of literary fiction, what would it be?

Read a lot and seek out and participate in a community of writers. That’s two things, but they’re related. A writing life is most sustainable when it’s not only about what you produce.

Your expertise with writing about trauma is impressive. If you were to give a five minute workshop on the five most important tips to tell survivors interested in retelling their stories, which five things would you select as most significant?

Interesting question. I’ve never thought about this. Let’s see….

- Write for yourself first. Don’t think about anyone else. Block them out. It’s only for you.

- Write where the heat is. Write into the darkness.

- Be kind and patient with yourself. Take breaks when you want to. Cry when you need to.

- And here’s something that really helped me: In addition to going deep inside my experience, I also tried to get outside of it. I researched child sexual abuse, pedophilia, rates of sex crimes, the law, anything I could think of. This helped me gain perspective on my story and see it as part of a larger whole, which grounded me.

Looks like I only have four. Well, I’ll use that first minute for an introduction. J

Which memoirists or creative non-fiction authors have influenced your desire to write The Telling? Which psychologists or therapists, famous or otherwise?

Very early on in the process, I read Vivian Gornick’s memoir Fierce Attachments, and I was transfixed by it. The way she wove sections of present-day conversations with her mother into the story about her past and her deep examination of crucial moments from her childhood gave me a template. Other memoirs I looked to for guidance included Lidia Yuknavitch’s Chronology of Water and Stephen Elliot’s The Adderall Diaries. Both of them opened up for form for me. A pivotal nonfiction book was The Trauma Myth: The Truth About the Sexual Abuse of Children and its Aftermath, by Susan A. Clancy, a psychologist who interviewed many adults who’d been sexually abused as children. Her work challenges some of the commonly help beliefs about the nature of childhood sexual trauma. Finding this book was so important to me that there’s a whole chapter about it in The Telling.

I’m interested in your work on trauma and the use of “telling” to destigmatize having discussions about how childhood abuse affects adult relationships, sexual and intimate. In addition to the narrative arc about your own story, you add factual evidence to the some of the chapters. Is it your hope the book will provide a dual function of informing readers about the intricacies of long-term effects in expository as well as personal ways?

Yes, absolutely. And this extends beyond the effects on people who’ve been abused to facts about childhood sexual abuse and pedophilia in general. The more I learned about childhood sexual assault, the more aware I become of how many myths about it still circulate. We’ll make much more headway on this problem if we dispel them. And we’ll be better able to call out instances where the fear and hysteria about childhood sexual abuse are used to enforce hate and prejudice, as is the case in North Carolina right now. The majority of children who are abused suffer at the hands of a relative or person well-known to them, mostly cis men, and the most common place for abuse to occur—just as it’s the most common place for rape to occur— is in a home. There’s absolutely no evidence that transgender people are a threat to the safety of women or children or anyone else. Offenders of every kind of sex crime are most likely to be cis men—though it’s also important to note that women can offend too.

Yes, absolutely. And this extends beyond the effects on people who’ve been abused to facts about childhood sexual abuse and pedophilia in general. The more I learned about childhood sexual assault, the more aware I become of how many myths about it still circulate. We’ll make much more headway on this problem if we dispel them. And we’ll be better able to call out instances where the fear and hysteria about childhood sexual abuse are used to enforce hate and prejudice, as is the case in North Carolina right now. The majority of children who are abused suffer at the hands of a relative or person well-known to them, mostly cis men, and the most common place for abuse to occur—just as it’s the most common place for rape to occur— is in a home. There’s absolutely no evidence that transgender people are a threat to the safety of women or children or anyone else. Offenders of every kind of sex crime are most likely to be cis men—though it’s also important to note that women can offend too.

I particularly enjoyed how the discussion of abuse survivors in both genders came up in your book, like here where you say: “Even men who acknowledge to themselves that they’ve experienced sexual violence might be reluctant to speak of it to anyone. Our culture assumes male sexual insatiability and sees the ability to protect oneself as a core element of manhood—making men even more likely than women, who also experience reservations about disclosing, to be ashamed by victimhood, or be fearful they won’t be believed.” Do you think the expectations for “manly behavior” are the same, worse, or better in America than abroad?

My experience abroad is limited, and my perceptions are probably influenced by stereotypes, but I’ll hazard a guess: We’re probably a bit better than average overall, with great variance across regions and social and cultural groups.

The discussion of gender roles is ongoing and particularly effective in this narrative when seen through so many filters. In the passage when the narrator discusses going on the road and taking a man along as protection against rape, a boyfriend, you pause to reflect on the way a sense of “danger” or “safety” can inform many women’s choices. Gender roles return to the narrative when you discuss how street people tend to engage with men, when men are present, as women are bantered or bartered over. Did you want this book to escalate the question of the role male privilege plays in every societal exchange?

My growing and shifting awareness of the way my gender affected how I moved through the world—or perhaps more importantly, how people expected me to move through the world—was a huge part of my development as a person. The issue of how gender affects our perceptions of safety and risk was particularly of interest to me. The way the threat of rape can be used to keep women fearful and immobile, for example, was something I wanted to examine and push against. But I hope the book also acknowledges the other factors that affected my ability to move freely—being a white American has given me greater mobility and a certain protection not granted to others, and at times my gender combined with my race and class has helped me gain entry. And when we focus on how vulnerable women are to sexual assault, we run the risk of overlooking the threat that exists for boys and men, too. The numbers of males who experience childhood sexual assault and rape are much higher than most of us realize. If we start to acknowledge male vulnerability, maybe we can break down some of the male entitlement and bravado that does so much harm.

The element of family weaves skillfully through the book as well. Do you think parenthood creates longer lens through which to view or tell stories about multiple generations?

That’s a natural conclusion to come to, and in my book I acknowledge that being postpartum when I learned that the person who had abused me as a child was now in jail awaiting trial for doing the same thing to another girl affected my reaction. I think the new responsibilities of parenting made me feel retroactively guilty for not somehow having been able to protect other children, and as each of my kids reached the age I had been when my abuse started, it brought up the issue for me again. But it’s sometimes hard to separate how much of our shifting perspectives are due to greater life experience in general from how much comes specifically from parenting. I remember having a heart-to-heart in my mid-thirties with two old friends. I was detailing changes in and attributing them to motherhood, but the friends had actually been changing in the similar ways even though they hadn’t had kids. It seemed to be more a stage-of-life thing. So I think the long lens can come from a variety of different circumstances.

Your work is quite brave. Bravo! Do you ever fear that a memoir is something you may regret at a later stage in life? Relatedly, how do you advise those for whom situations they may publish about will create new ripples in interpersonal situations with family members, outside readers, or anyone they encounter who reads the work?

When I started getting tattoos in my late teens and twenties, people would often ask me whether I worried I’d regret it when I turned forty. I guess forty is considered to be some milestone of sense and truly adult maturity. Well, forty came and went some years ago, and I don’t regret my tattoos. The blurry ink is part of me, and I accept myself. I don’t expect to regret this memoir, either; it’s a part of me too. If I’m not old enough now to make an informed decision, when will I ever be?

But yes, writing a memoir can be a risk. Reaching a place of self-acceptance is crucial to any writer who’s working with personal material, and then being thoughtful about what you’re doing on top of that. I spent a lot of time considering the perspectives of the people I was writing about—how they might be viewed by readers and how they might view things. Was I being fair? I’m sure there are plenty of reasons why people can be upset by the book, but at least I know I tried my best to uphold my own standards.

Writing a memoir is such an intimate pursuit. Do you think you’ll write another?

I have no plans to. Certainly I feel like I’ve wrung as much narrative out of my childhood and coming of age as I care to. But maybe I’ll find my way to another kind of nonfiction project that flips the balance of this one—requiring some personal narrative but more research. What I’m most excited about right now, though, it returning to writing a novel that I started a couple years ago. It’s completely different from anything I’ve written and is the opposite of a memoir—a sort of fantasy almost-dystopia set in the near future, where memory and fact don’t come into it at all.

Writers on Craft is hosted by Heather Fowler, who cares about writing. She does a lot of it. Visit her profile on Fictionaut or see here for more: www.heatherfowlerwrites.com.

No Comments

Leave a Comment

trackback address