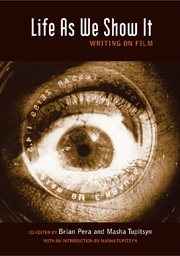

Masha Tupitsyn is the author of Beauty Talk & Monsters, a collection of film-based stories, and co-editor of the anthology Life As We Show It: Writing on Film, a cross-genre collection that uses short stories, essays, and poetry to explore the cinematic experience. She also writes daily film criticism on Twitter using only 140 characters. The following is an excerpt from Masha’s introduction to Life As We Show It.

When I met Brian Pera, my co-editor, in December of 2005, it was through email, the equivalent of coffee or drinks in the cyber world. Brian wrote me a missive in response to a formal inquiry I’d made about submitting to his online journal Lowblueflame. The last issue he edited, which was still up on his website at the time, featured some of the writers in Life As We Show It and was dedicated to the movies. The untitled issue of Lowblueflame, which I refer to as the “déjà vu issue,” was an exercise in cinematic hearsay. Tracing his own celluloid obsession, a curiosity informed in equal measure by movies seen and unseen, Brian asked each writer to describe a film based on what they’d read and heard about it. If I’d been able to participate, I would have recounted my own movie déjà vu (a word that literally means “already seen”), Don’t Look Now, which I’d seen on TV but didn’t remember seeing until years later, when I overheard someone describing what I thought was a private terror: a red-cloaked monster-dwarf haunting Donald Sutherland in the catacombs of Venice. At the time, my cinematic references were much more limited: I knew who Donald Sutherland was, but not Julie Christie (I had not yet moved to London or discovered the British New Wave). The name Nicholas Roeg didn’t ring a bell. But based on the villain sketch, and the red hoody on the little girl next to me, I immediately recalled the iconic movie I’d seen a clip of as a six year old, rather than the private “memory” fragment I had catalogued it as all those years.

When I met Brian Pera, my co-editor, in December of 2005, it was through email, the equivalent of coffee or drinks in the cyber world. Brian wrote me a missive in response to a formal inquiry I’d made about submitting to his online journal Lowblueflame. The last issue he edited, which was still up on his website at the time, featured some of the writers in Life As We Show It and was dedicated to the movies. The untitled issue of Lowblueflame, which I refer to as the “déjà vu issue,” was an exercise in cinematic hearsay. Tracing his own celluloid obsession, a curiosity informed in equal measure by movies seen and unseen, Brian asked each writer to describe a film based on what they’d read and heard about it. If I’d been able to participate, I would have recounted my own movie déjà vu (a word that literally means “already seen”), Don’t Look Now, which I’d seen on TV but didn’t remember seeing until years later, when I overheard someone describing what I thought was a private terror: a red-cloaked monster-dwarf haunting Donald Sutherland in the catacombs of Venice. At the time, my cinematic references were much more limited: I knew who Donald Sutherland was, but not Julie Christie (I had not yet moved to London or discovered the British New Wave). The name Nicholas Roeg didn’t ring a bell. But based on the villain sketch, and the red hoody on the little girl next to me, I immediately recalled the iconic movie I’d seen a clip of as a six year old, rather than the private “memory” fragment I had catalogued it as all those years.

By confabulating movies they hadn’t actually viewed, the writers in Lowblueflame concocted parallel pictures, plots, and narratives. In many of the stories, subtext is teased and stretched until it possesses the official narrative, filling and swallowing it like the amorphous creature in The Blob. Life-long Jaws fanatic, and one of the maker’s of the yet-to-be released 2006 documentary The Shark is Still Working: The Impact and Legacy of Jaws, narrated by Roy Scheider, Erik Hollander writes about the many different ways movies can be viewed:

It was a full three years later when I finally got to see Jaws on the big screen during its re-release in 1978. In the years between, I had obsessed about what I had come to imagine the film to be like. I based my ‘vision’ of the scenes on three years of playground chatter from those lucky classmates that were allowed to see it – which was everyone else! Despite having conjured up a pretty impressive picture in my mind about the movie, finally watching the real deal with my dad on that fateful afternoon in July replaced my misinterpretations with imagery that exceeded my wildest expectations. That day has never left me. When Jaws finally aired for the first time on network television, my dad set up a cassette recorder and taped the audio for me, and for the next Lord knows how many years, I listened to that cassette every single day until the magnetic signal wore away. Every line, every sound effect, every music cue has been seared into my memory ever since. So, for me, Jaws has always been more of a personal life experience than merely a favorite film.

In his book What Do Pictures Want? W.J.T. Mitchell treats images as living things with personalities, demands, and desires of their own, stating, “To get the whole picture of pictures, we cannot remain content with the narrow conception of them.” Part of the incentive for Life As We Show It was to use film, and the culture that comes with it, as an ingredient for narrative impetus-for writing, for imagining, and for thinking. Movies are starting points, like any subject or theme, in order to enter into the culture that’s inside of them as well as the culture that inside of us. For me, film writing, as opposed to straight film criticism, is a way for an author to merge with not just the thing they write, but the film they’re looking at, so that writing becomes both cultural analysis and personal revelation. Since on-screen and off-screen constantly overlap and get mixed up, writing about images becomes most interesting when it attempts to reflect this blurring through form and content. When it allows the writing to be transformed and shaped by what it writes about.

No Comments

Leave a Comment

trackback address