Klonakilty

by Steven Gowin

Magdalena White Herrington praised the lucky seas who'd washed her the Klonakilty[1] ghosts.

In Spring 1965, at age 17, against her will, she'd married John Herrington II and was pregnant with his child a month later.

All had occurred at Mother Irma White's insistence and according to her idea of what good girls should do: confirmation, thrice weekly mass (at least), daily rosaries, and the Herrington marriage.

After the wedding, Madge and Jackie moved to Klonakilty. Old Man Herrington and Mother White had decided the newlyweds should look after that dairy and be alone and had summoned a special priest from Dublin to “bless” the cottage. Although Madge supposed it connected to expectations of a grandson, Father Kerrigan's vigorous and pious mojo had frightened her.

Learning of the marriage from his savannah outpost, Madge's father, Desmond White, refused to bless the union. He'd seen those Herringtons bully and strong arm Beara neighbors and contended that Old John, the old man, would as soon force a family off its land as sneeze. Hadn't they driven the Whites off their own place at Eskivaude with a fishy mortgage loan?

For their part, the Herrington ilk contended that Dessie'd no claim on the girl, no say in issues Madge; why, he barely knew the child, did he? Hadn't he divorced Irma and spent months, years away on military work, soldiering for Mike Hoare and Bob Denard[2] and Sir Percy Stilltoe before the others? What kind of father was this?

Still, in Fall 1965, on a rifle shot gam, Desmond arrived home from Buta, Haut-Congo to recover and reconnect with Madge. Boa phantoms and unspeakable memories haunted him, and he confided the nightmares to Magdalena. Meanwhile, he demanded that Herringtons treat her with the respect they'd never shown Whites in the past. And he promised to murder any of them who did not.

As the birth neared, Jackie spent more days with his father five miles and forty years' progress over the Caha Mountains from Klonakilty. The treeless countryside at Coomeen produced sweet grass and fine milk, and the old man's cottage was warm and comfortable. On squall-plagued Kenmare Bay though, Klonakilty had never been electrified, had no running water, and no heat save its coal burning stove.

Nevertheless, Madge ran the tidy operation her mam required and tended the cows as Old Man Herrington prescribed. She'd only finished the primary grades but kept a head on her shoulders and understood wind and light and dairy. She fetched water from the deep well every morning, and she hung Jackie's hand-laundered cow clothes outside to dry between gales.

Klonakilty's isolation simultaneously fascinated and frightened her. With its tiny protected harbor and white strand, the hamlet had hosted several generations of Egan fishermen. Madge had no idea how they'd all survived, but knew the story of their demise.

On Christmas Eve 1922, a gale had blown up quick and furious off the wild Atlantic. At sea, it cleft the great Skellig Rock then blew up Kenmare Bay to claim roofs near Blackwater Bridge and wash away the Coss Strand. Those Egans had been out to poach the yuletide salmon when the hurricane's wrath drowned all of them save one.

Afterwards, the only trace of fisher left, Billy Egan, had washed up at Klonakilty 50 yards from Madge's kitchen window. Unsure of his mortal condition, poor Billy had ranted three days and a half about the wreck and all those dead fishes and uncles and brothers washing about him bootless, puffy and white, tempest stripped, naked at sea.

When he was able, he and the rest of the Egans abandoned Klonakilty for some desert place in America far far from water. Herringtons had snapped up the property, and from then on, the only visitor was the occasional squatter, a tinker who some Herrington or other and the Garda eventually ran off.

It was a short December afternoon when a very pregnant Madge had gathered in the still damp laundry, swept and scrubbed the upstairs bedroom, emptied the chamber pot, and oiled and polished the corner settle before finding the cows to milk. Boss, boss, boss, she'd cooed into the heavy blowing air, and the cows had come quickly. But in the milking, one after another gave near nothing and that already gone sour.

Madge checked bovine eyes and mouths, but all seemed well. She'd need tell Jackie when he got home, and he'd surely rage about the trouble. But the barometer was dropping quickly, another gale blowing in, maybe that was it. So with cows in their stalls, she started down the path to the house. The rain and wind had begun by then, and with the day nearly gone, she walked gingerly.

The child felt heavy in her now and kicked hard, and when Madge looked up, she noticed a yellow glow a couple hundred yards distant on the the water. Who'd be out now with this weather coming? She'd left no light in the cottage, so once inside she fired a petrol lamp. She'd go upstairs for a jumper before putting out the supper.

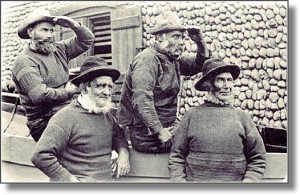

And so passing through the house, light hissing before her, she found the four men on her settle. Each wore a wet black slicker and storm hat pulled below his eyes. Each appeared to be naked under his coat. Each sat bootless, bare white legs and feet swollen and wet. She hoped they expected no supper, but none spoke. Madge lowered the lantern and realizing the visitors' identity, wanted nothing but to scream, but her throat clenched, she could not cry out.

Finally, after time enough to smell the brine in the room, Madge turned away and carefully climbed to the bedroom above, all the while dreading what she'd find. But no one and nothing occupied her room. Breathless, smothering, she gently closed and latched the door behind her. A deathly cold, heavy as the sea, seeped into her until she pulled down the covers, got into bed, and gathered the blankets tight over her.

Able to scream now, she muffled her cries with a pillow, then prayed fervent rosary after rosary for her baby's soul, for her own, and for souls of all the drowned fishermen below. Terrified of gods and demons and frigid worlds unseen, a horrible sleep did overtake her, and she did dream of tridents and piked Bantu heads and rotting salmon in the water.

When he arrived back at Klonakilty, no supper awaited Jackie, and Madge's absence and clear inattention angered him. Had she even tended the cows? He looked for her and seeing light under the bedroom door, he rattled the latch. Madge finally opened up.

Groggy from the bad sleep and still terrified, she tried to explain what she'd seen. But Jackie refused to believe her. He said she'd come upstairs after the milking and put her head down and dreamt this horrible thing. In fact, she probably hadn't even finished the milking.

He called her lazy and swore this silliness must end. His father said it was time she grow up. She'd soon need look after the cattle and Jackie and his baby boy. Come downstairs then, Jackie insisted. But Madge refused. She knew what she'd seen.

She reckoned that Jackie only worried about her as he'd worry about one of his pregnant cows, as if she were no more than breeding stock, but she'd be ignored no more, and she told him so. She said she was done with him and his father and all Herringtons forever.

With that Jackie grabbed her by the arm. She was coming with him, by God, and when Madge dug in, he struck her hard. Then he dragged her by her hair to the kitchen, the mudroom, the workshop, and the parlour.

Nothing and no one. Madge had been crying hard, but as soon as she noticed the puddles, a calm, a near contentment, overcame her. Under the settle, where the fishermen had waited, four icy splotches pooled on the floor. Jackie let her go. Madge bent and dipped a finger and tasted. Salt. Was that not enough?

But Jackie, confused for a moment, rebounded and accused her of spilling the water to trick him. That's when Madge turned and went for the big kitchen knife. Once she'd found it, she stood motionless a beat, shifted the blade from right to left hand, from left hand to right. She paused but then slowly, coldly, dragged her own finger, the one she'd tasted for salt, under the blade's razor edge.

Then she approached Jackie, reached out with the lacerated finger, and soothed thick hot blood onto Jackie's cheek. She'd speak to her father tomorrow, she said, and Herringtons might expect murder in the night, that's all. Startled now and again confused, Jackie said she must be crazy, possessed, that that damned Kerrigan'd done no good at all. He gathered his things and was gone.

Madge did contact Dessie, and that next afternoon he walked the seven miles from Allihies to Klonakilty to be with his daughter. Two weeks later, on Saint Stephen's, Madge delivered his baby grandchild.

That night, the birth night, another stormy one, the fishermen visited Madge again leaving a bright fresh salmon. But this time they neither frightened nor chilled her. She'd first thought to name the baby Gale, but thought better and christened the the little girl, Egan.

She knew that when her mother and the Herringtons and the rest heard of the delicate translucent webs between Egan's toes, they'd vex neither child nor mother nor grandfather nor any of the Whites or Klonakilty ghosts again.

____________________

[1] Not to be confused with Clonakilty near Bandon

[2] Hoare's 5th Commandos conquered Buta, Congo with Denard's mercenaries from the 1ere Choc in June, 1965 during the Congolese Civil Wars. Sir Percy Stilton conducted diamond wars for De Beers in Sierra Leone in the fifties

|

13

favs |

981 views

14 comments |

1704 words

All rights reserved. |

Author's Note

Other stories by Steven Gowin

Tags

This story has no tags.

Great tale well told.

Agree with Gary.*

Yes, indeed. Nice work, Gowin!*

**

Great storytelling, great story! And the prose is a pleasure to read.

* Oh! Oh! Just the right taste of brogue to it, too.

I liked it, a lot, but held my virtual tongue until Claffey weighed in, and now I can say, Nice work, Gowin! *

That's some fine storytelling. Fine, fine, fine.*

*, Steven. A really fine story, well-written, proving you can handle the culture without wearing an Erin go bra.

I don't usually read something this long on my phone. I'm glad I did this time. Great work. *

Crazy! You made me believe in ghosts. I blame you, Gowin: I blame you. *.

A well-woven yarn!

oh, *

Okaaaaaay.... ***