We are pleased to welcome American journalist and versatile author Miles Harvey to Writers on Craft today. Harvey has a B.S. in journalism from the University of Illinois and an M.F.A. in English from the University of Michigan. He has worked for United Press International, In These Times and Outside on a variety of topics and issues. One of his stories for Outside served as the basis for the 2000 book, The Island of Lost Maps, which recounted the strange story of a Floridian who stole many old and precious maps from various libraries across America and was named one of the top ten books of 2000 by USA Today and the Chicago Sun-Times. He is also the author of Painter in a Savage Land: The Strange Saga of the First European Artist in North America, a non-fiction work that explores Jacques Le Moyne de Morgues‘s adventures with the French expedition to Florida led by Jean Ribault during the sixteenth century. His fiction has appeared in publications such as Ploughshares, AGNI, The Michigan Quarterly Review, Fiction Magazine and The Sun, and has received a Distinguished Story citation in Best American Short Stories, 2005, and a Special Mention in Pushcart Prize XXXVII: Best of the Small Presses, 2013. He teaches creative writing at DePaul University.

We are pleased to welcome American journalist and versatile author Miles Harvey to Writers on Craft today. Harvey has a B.S. in journalism from the University of Illinois and an M.F.A. in English from the University of Michigan. He has worked for United Press International, In These Times and Outside on a variety of topics and issues. One of his stories for Outside served as the basis for the 2000 book, The Island of Lost Maps, which recounted the strange story of a Floridian who stole many old and precious maps from various libraries across America and was named one of the top ten books of 2000 by USA Today and the Chicago Sun-Times. He is also the author of Painter in a Savage Land: The Strange Saga of the First European Artist in North America, a non-fiction work that explores Jacques Le Moyne de Morgues‘s adventures with the French expedition to Florida led by Jean Ribault during the sixteenth century. His fiction has appeared in publications such as Ploughshares, AGNI, The Michigan Quarterly Review, Fiction Magazine and The Sun, and has received a Distinguished Story citation in Best American Short Stories, 2005, and a Special Mention in Pushcart Prize XXXVII: Best of the Small Presses, 2013. He teaches creative writing at DePaul University.

What do you read when you despair at the state of either your work or modern literature–any “go to” texts?

I don’t ever despair at the state of modern literature; there are just too many writers doing exciting work right now. Just this week, I finished three books that blew me away–Peter Orner’s short-story collection Last Car Over the Sagamore Bridge, Roberto Bolaño’s novel Monsieur Pain and Michael Paterniti’s sublime work of creative nonfiction, The Telling Room. I’m also reading a stunning draft of an unpublished novel by Scott Blackwood, who won a Whiting Writers’ Award a year or two back. His daring first novel, We Agreed to Meet Just Here, is easily one of my favorite books from the last few years. It came out on a university press, so not that many people have read it, unfortunately. But I couldn’t recommend it more highly to all you Fictionaut authors and readers out there.

Some of my go-to writers: Virginia Woolf, W.G. Sebald, José Saramago, António Lobo Antunes, Alice Munro, Charles Baxter and Raymond Carver. Oh, and Borges! I can’t get enough of Borges.

If you could give just one piece of advice to emerging authors about editing that has served you well, what would it be?

When I was a magazine editor, it took about two seconds to tell the amateurs and the dabblers from the professionals. The pros embrace editing, and they know when to pick fights. They tend to see editors as collaborators—and they understand that editors often save writers from their own weaknesses and blind spots. The amateurs argue over every last comma and semicolon; their precious prose is sacrosanct. So I guess my advice would be to listen to, and learn from, editors. At least 75 percent of the time, they have your best interests in mind. Another 20 percent of the time, they have the publication’s best interests in mind, in which case you’re unlikely to win an argument with them anyway. The trick is to learn when, and under what circumstances, to put your foot down.

How has your perception of what you “do” with your work changed as you have continued to write?

I’ve always had a fairly wide range of literary interests and ambitions, so I don’t spend a lot of time worrying about what I “do.” I have an undergraduate journalism degree and an MFA in fiction. My books are nonfiction, but I’ve always written and published a fair amount of short stories, and I teach both genres.

I’ve always had a fairly wide range of literary interests and ambitions, so I don’t spend a lot of time worrying about what I “do.” I have an undergraduate journalism degree and an MFA in fiction. My books are nonfiction, but I’ve always written and published a fair amount of short stories, and I teach both genres.

This year, with the premiere of a piece at Steppenwolf Theatre in Chicago, I became a playwright. I also edited a book for the first time. So I suppose I would say I’m still evolving. I hope so, anyway.

What do you feel is the purpose of poetry/literature?

What isn’t the purpose of poetry and literature? I’m not sure poetry and literature need to justify or explain themselves. They pretty much make life worth living.

As a human being, what is the best advice you have to offer?

A friend recently gave me a bumper sticker that says DON’T BELIEVE EVERYTHING YOU THINK. Much to my surprise, my wife went right out and slapped that thing on our Kia Soul. I’ve never been much for maxims, especially of the pop-philosophy variety, and I’ve always associated that sort of bumper stickers with earnest, unbathed do-gooder types. “Are you trying to make everybody think we’re from Oregon?” I asked my wife.

For a long time, that sticker would cause me to cringe every time I glanced at it. But lately, I’ve sort of begun to embrace it, in part because I’ve noticed some of my middle-aged friends becoming more and more rigid in their world views.

Don’t believe everything you think—I’m not sure it’s the best advice I have to offer about being human, but it’s far from the worst, especially for writers.

Your work is heavily influenced by setting. Do you feel that an author who explores the locations of their work is more likely to reach a universality of appeal due to this focus on place?

The thing is, you don’t normally reach universality by writing about the universal. Faulkner’s stories and novels, for example, are universal precisely because they are so grounded in the local. Yoknapatawpha County is a real place to readers. We see it, we hear it, we smell it, we feel it in our bones. And because it is so vivid and concrete, we recognize it as somehow our own, even if we’ve never been within 1,000 miles of Mississippi.

Perhaps the thing that perplexes me most as a teacher of creative writing is how little attention many of my students pay to setting. In 1996, a literary magazine editor named Joan Connor wrote a prescient essay, “In the Middle of Nowhere,” in which she observed that the submissions she was receiving increasingly lacked a precise sense of place:

“One development which I have noted is the generic setting. Farm stories abound, as do school stories, unidentified city stories, and apartment stories. But the barns, schools, cities, and apartments are interchangeable; they have no individuating characteristics. The setting seems to be inserted like an afterthought from the outside rather than be integrated into the story.”

My sense is that setting has only gotten more generic in the nearly 20 years since Connor wrote those words. I’m not sure quite how to explain it, but I see tons of those “school stories” and “apartment stories.” In one sense, they are universal (a word that comes from the Latin for “of or belonging to all”) but in a much more profound sense they are soulless and empty. Because they belong to nowhere, they also belong to no one.

What’s recently released or in the pipeline for your readers? Give us a sneak peek.

I’m just finishing a project that has consumed me for the past three years. During 2011 and 2012, while more than 900 people were being murdered on the streets of Chicago, my creative-writing students and I fanned out all over the city to interview people whose lives have been changed by the bloodshed. We spoke with kids in gangs and kids trying to stay out of gangs. We spoke with mothers and fathers of young people who had been killed. We spoke with police officers and teachers and members of the clergy and murderers. We spoke with an emergency-room nurse and the county coroner and a funeral-home director.

When we began the project, I reminded the students that we live in a world where everybody’s talking—blogging, texting, tweeting, Friending, shouting each other down—but nobody’s really listening. So that was their assignment: just go out and listen.

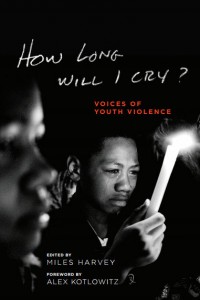

They came back with thousands of pages of interview transcripts–and the stories were just amazing. I took some of those stories and wove them together into a play, How Long Will I Cry?: Voices of Youth Violence, which premiered at Steppenwolf Theatre earlier this year.

We also put together a book of Studs Terkel-type oral histories, which will be published this fall. It’s a powerful collection, and I’m amazingly proud of the work my students did on it. Here’s a trailer, created by a DePaul graduate student:

I’m setting aside free copies for the first 20 Fictionaut readers who e-mail book.project@depaul.edu. (Please note where you read about the book.) We’re also making copies available at no cost for librarians and teachers across the country.

Writers on Craft is hosted by Heather Fowler, who cares about writing. She does a lot of it. Visit her profile on Fictionaut or see here for more: www.heatherfowlerwrites.com.

Sep 19th, 2013 at 9:19 am

Good, meaty stuff. I liked particularly his thoughts on the use of place in fiction.

Sep 25th, 2013 at 11:04 am

I appreciate so much about this post, Miles. My daughter was seven (now she’s 17) when she insisted on buying a Don’t Believe Everything You Think bumper sticker in Berkeley in 2003. Also, I’m excited about the Studs Terkel collection; I’ve been a huge fan all my life. The work you’re doing for Chicago is moving and necessary. Thank you very much for making my day!