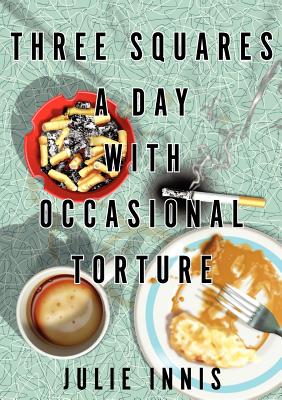

First a confession: my vision hasn’t been so hot for the last few years, which means reading hasn’t been a pleasure for quite a long time. Last night, I read Julie Innis’s Three Squares a Day with Occasional Torture from cover to cover in one sitting, never losing a second thought about my vision. Brava, Julie Innis! I’m healed.

Or I should say the voices Innis creates have healed me. And maybe I should add the curative powers of dark humor. You know fiction can heal when you tell someone, “I read this hilarious story about this aging play-cop loser forced to part with his surrogate son—a chimp rescued from a lab—because of his mother’s promiscuity,” and this someone says, “Wow, that’s kind of sad actually.” “No!” you say. “It’s like Fargo. You know. The scene with the shredder?” And you both fall about laughing. Here’s the last paragraph of “Monkey”:

I didn’t explain to her that Monkey wasn’t suited for the world, that he lacked street smarts and I worried that at night he’d be afraid, the sounds of tigers below, their ears pitched toward the little whistling noise his nose made when he breathed. I think of Monkey still and hope he’s making out okay. Sometimes late at night when I’m on rounds, I pull the scanner’s microphone all the way out to its end and then I just let it go.

I feel for this tragic figure, and I think you do as well. We have to laugh, though. That’s how we deal with our tragic world.

The great short story writer has the ability to create not just one tragicomic world but lots of them. Three Squares a Day with Occasional Torture includes nineteen of Innis’s worlds, each with memorable, mostly tragic characters, all trying to make sense of life and some stretching the boundaries of magical realism. If magical realism is an art of surprises, Innis makes it an art of satisfying ones. I especially like the arrival of Annie in “Gilly the Goat-Girl,” a surprise I’ve decided not to ruin for you. Instead, here’s the opening paragraph of this brilliant tale of maternal love and misguided fashion choices:

I’ve never had much success with men. I’m sure it all goes back to my parents’ divorce. At least, I assume that’s what a therapist would tell me. Temping provides me with very basic health insurance, so mental health services aren’t covered. Grease burns, broken limbs, venereal diseases—check, check, and check. Ennui, angst, and depression—better just keep a mattress out under your window because no one’s going to be there to talk you in from the ledge.

I think this paragraph sums up the collective consciousness of Innis’s characters. They populate worlds where all the safety nets have holes, where you can bet the firemen will move the net away if you jump, where relationships don’t work. To say the characters’ relationships are dysfunctional would be so 1985. Innis’s characters are done with dysfunctional; they’re post-dysfunctional. They yawn at dysfunction. These worlds are void of sentimentality and answers,

At university a “few” years ago, I read Sherwood Anderson’s Winesberg, Ohio: a Group of Tales of Ohio Small-town Life. Just as Anderson assembles the quirky inhabitants of a single and fictitious community in Ohio, Innis gathers her cast on a continuum from Ohio to Brooklyn. There are no recurrent central characters and each story stands alone, but there are central themes: weariness with a world that doesn’t quite work, preoccupation with health problems, social problems, job problems . . . problems. But we still laugh. Anderson dealt with similar themes but through the decidely less humorous lens of 1919 realism. The glue that holds Three Squares a Day with Occasional Torture together is Innis’s community of broken-yet-strong characters, but it’s also her daring wit, her timing, and her enviable—humorous—dialogue.

Humor is like a tight-rope made of razor blades. Some writers who try it come away with more cuts than it’s worth. Innis dances on razors. And she does this by being generous to her characters, indulging their whims, allowing them to be bizarre in their humanity, human in their absurdity. And this is the key to believably, an element of good fiction that eludes so many writers.

I’m particularly fond of the dialogue between Heller and Goldfarb in “Heller.” Innis pits Heller’s jealously against Goldfarb’s adolescent confusion so well. The dialogue in “Do” is pleasingly ballsy and Palahniukesque, and I hope both Innis and Palahniuk are mutually complimented by ballsy. It’s astounding how much Innis can do with such dialogic brevity in “Blubber Boy.”

I can’t end this review without talking about Innis’s female characters, who are chopped in half, turned into cars, corrected and of course tortured. It’s not so much that they are in many ways abused, ignored and misunderstood by men; these stories are more about a woman’s reaction to their worlds and their men. I think this point of view is best summed up in “The Next Man”:

The next man will be better, she hoped. He’ll belch and fart and slouch in his seat. She’ll twine her fingers through his rough pelt, put braids in his thick hair. They will eat their meat rare; they’ll tear it lustily from the bone.

Disappointment with men is a theme that ties many of these stories together: from “My First Serial Killer” about an inept killer and his bored victim, to “Habitat for Humility” about a couple subjected to prejudice because of the husband’s conspicuous consumption, and ending with “Fly,” a love story between an unsatisfied wife and a fly.

Three Squares a Day with Occasional Torture is a contemporary community of characters—some grotesques, some from the heights of magical realism, some realistic portraits of men and women doing their best to cope with contemporary issues, searching for the way of Do but finding only an oversexed Sensei Vinnie telling them that “For every ass-kicker, there’s an ass. Yin and Yang.” In essence, don’t be such a pussy.

Julie Innis’s fascinating book Three Squares a Day with Occasional Torture is available from Amazon and Powells.

Christopher Allen, a native of Tennessee, lives in Germany. His fiction and creative non-fiction have appeared in numerous places both online and in print. In 2011, Allen was a Pushcart Prize nominee and a finalist at Glimmer Train. He blogs at www.imustbeoff.com.

Nov 29th, 2012 at 5:17 pm

Julie’s book is worthy. You should buy it. Really. Buy it now.

Dec 3rd, 2012 at 11:01 am

A review that in its crisp appreciation for all the fine points of Julie’s great book really does it justice. Buy it. Read it.