1.

I am against social networking sites but I am for them. I have made no secret of my opinion.

1a.

When making a broad and possibly indefensible argument about an impersonal technology, it is customary to begin with a personal anecdote. In the last year I have experienced a strange phenomenon in which more than a few close friends have concealed the existence of new relationships. I will invent an example so as not to embarrass anyone. My friend Roddy started dating a woman about two months ago. I have known him since 1990, and in the past, whenever he has started dating a girl, he has brought her around, introduced her to our group of friends: “This is Nancy,” or “This is Susan,” or “This is Allison,” or “This is Leah.” You get the idea. But in the last year, on two separate occasions, he has been dating a girl for more than a month and kept it to himself. The first time, I didn’t think much of it. Maybe he thought that she wouldn’t like the rest of us, or vice-versa. Maybe he worried that she looked similar enough to a former girlfriend that a comment would be made. But the second time it happened, I thought much of it, especially since the same thing was happening at the same time to a female friend of mine. Once seems like a blip. Twice seems like a bloop. More than twice, with more than one person involved, well, that’s a blurp, and a blurp merits further investigation.

2.

I am convinced the culprit is social-networking tools. They should vanish in a hail of fire before they poison our species further.

2a.

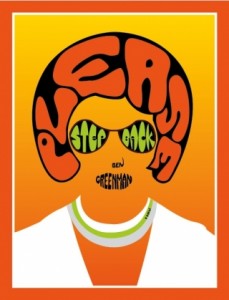

When making a violent and entirely facetious suggestion about a technology that others appear to enjoy, it is customary to soften the blow with a little story. A few weeks ago I was out in the western part of the United States, doing a pre-publication tour for my new novel, Please Step Back. The novel is good, I think, and will entertain some readers and enrich others. But I bring it up because it’s also useful in this piece. It takes place in the nineteen-sixties and nineteen-seventies. The main character is a funk-rock star named Rock Foxx who spends most of the book (and most of his life) trying to balance his desire to interact with others with his desire to protect his private space. He depends upon his celebrity but he hates it. He feeds off of his connections with others but they drain him. And today, thirty years after he existed, technology gives any ordinary human in any ordinary town the global reach that he fought for a solid decade to acquire. When I was out on tour, much of the publicity for the tour took place over social networks: Facebook, Twitter, blogs. Some of the people who posted or tweeted, before or after, showed up at my events, and for the first time, I noticed a steady stream of what I will now call “extroverted introverts,” shy people who were using these new technologies to broadcast their shyness to the world. Some of them came to my readings, didn’t even come up to talk to me, and then recounted their experience on their blogs or on their Twitter feeds. This is fine in some ways. It is good in some ways, even. It enables a kind of democracy of experience where an average experience is every bit as valid, and potentially as valuable, as a privileged one. I understand that. In that sense, I am in favor of these technologies. But I think it’s indisputable that these tools change the way that people view themselves with regard to the world around them. If I had to guess, I’d hypothesize that the steady stream of personal updates and dispatches has made people charier of disclosure. This seems paradoxical, but it’s actually logical: with so much out there and out of control, it makes sense to protect a few patches of emotional reality. I think that my friend Roddy, or the other friends I haven’t named, are more secretive regarding their relationships because they don’t trust the spread of information. Information wants to be free, and everyone wants to be enslaved to that free information, irrespective of its truth, its value, or its appropriateness. These extroverted introverts are more exposed than ever, but also more protective than ever because that exposure cannot be sanely or safely regulated. The result is a broad ontological shift, a turning inside-out, where the information that should be hidden is shared and the information that should be shared is hidden. My friend Roddy feels perfectly comfortable tweeting or changing his status update to tell me that he is ambivalent about baths, or that he is watching a lizard on his windowpane, but he is reluctant to introduce me to his new girlfriend. More interestingly, he may add his new girlfriend as a friend on Facebook and possibly even change his status cryptically to indicate that he is involved, but he will not bring the real human around. If this is any indication of future trends, and I think it is, these social-networking technologies will prove corrosive to coherent identity and narrative. It gets harder to draw lines between things when the units get smaller and smaller, and when the lines themselves are more and more dotted. Recently, I wrote a book of short stories about the loss of letter-writing and the larger related losses, and when I talked about the book in interviews, one of the examples I gave concerned identity. Fifteen years ago, when you sent me a letter, I received it three days later, and it was my responsibility to believe that the emotions you represented in that letter were still in fact valid. If you wrote “I’m angry at you,” I had to believe that you were still in some sense angry, and you had to believe it, too, or else you came apart at your own seams. Emotions and states of mind persisted, which was healthy for us all, because the alternative is too entropic. Now updates can be issued hourly, or even more minutely than that, and these ongoing amendments to the self cannot help but erode or erase broader outlines. Now that individuals can announce that they are angry and immediately announce that they are no longer angry, what is anger, and what are individuals? This may be a second reason why people like my friend Roddy don’t make real-world announcements about their real-world relationships. Those things are more definite and less ephemeral than status updates. Deciding upon them requires more effort, as does changing them. Real pain may be involved, as well as real painkilling. The online world, by contrast, is a cyclical (non)painkiller: it cures loneliness by creating a more profound loneliness. And while it is easy to imagine a more complete or compelling account of this process, it is also easy to imagine a world that, moving forward, is hostile to patience, pacing, or psychological complexity. I have told people this and they have laughed at me. They have said “old young man” scornfully. We will see. All I can say for certain is that many of the struggles in my novel—and the real events in my life to which they correspond—would not make as much sense in a world where news about the self is commonly dispatched via Twitter: again, inside-out.

When making a violent and entirely facetious suggestion about a technology that others appear to enjoy, it is customary to soften the blow with a little story. A few weeks ago I was out in the western part of the United States, doing a pre-publication tour for my new novel, Please Step Back. The novel is good, I think, and will entertain some readers and enrich others. But I bring it up because it’s also useful in this piece. It takes place in the nineteen-sixties and nineteen-seventies. The main character is a funk-rock star named Rock Foxx who spends most of the book (and most of his life) trying to balance his desire to interact with others with his desire to protect his private space. He depends upon his celebrity but he hates it. He feeds off of his connections with others but they drain him. And today, thirty years after he existed, technology gives any ordinary human in any ordinary town the global reach that he fought for a solid decade to acquire. When I was out on tour, much of the publicity for the tour took place over social networks: Facebook, Twitter, blogs. Some of the people who posted or tweeted, before or after, showed up at my events, and for the first time, I noticed a steady stream of what I will now call “extroverted introverts,” shy people who were using these new technologies to broadcast their shyness to the world. Some of them came to my readings, didn’t even come up to talk to me, and then recounted their experience on their blogs or on their Twitter feeds. This is fine in some ways. It is good in some ways, even. It enables a kind of democracy of experience where an average experience is every bit as valid, and potentially as valuable, as a privileged one. I understand that. In that sense, I am in favor of these technologies. But I think it’s indisputable that these tools change the way that people view themselves with regard to the world around them. If I had to guess, I’d hypothesize that the steady stream of personal updates and dispatches has made people charier of disclosure. This seems paradoxical, but it’s actually logical: with so much out there and out of control, it makes sense to protect a few patches of emotional reality. I think that my friend Roddy, or the other friends I haven’t named, are more secretive regarding their relationships because they don’t trust the spread of information. Information wants to be free, and everyone wants to be enslaved to that free information, irrespective of its truth, its value, or its appropriateness. These extroverted introverts are more exposed than ever, but also more protective than ever because that exposure cannot be sanely or safely regulated. The result is a broad ontological shift, a turning inside-out, where the information that should be hidden is shared and the information that should be shared is hidden. My friend Roddy feels perfectly comfortable tweeting or changing his status update to tell me that he is ambivalent about baths, or that he is watching a lizard on his windowpane, but he is reluctant to introduce me to his new girlfriend. More interestingly, he may add his new girlfriend as a friend on Facebook and possibly even change his status cryptically to indicate that he is involved, but he will not bring the real human around. If this is any indication of future trends, and I think it is, these social-networking technologies will prove corrosive to coherent identity and narrative. It gets harder to draw lines between things when the units get smaller and smaller, and when the lines themselves are more and more dotted. Recently, I wrote a book of short stories about the loss of letter-writing and the larger related losses, and when I talked about the book in interviews, one of the examples I gave concerned identity. Fifteen years ago, when you sent me a letter, I received it three days later, and it was my responsibility to believe that the emotions you represented in that letter were still in fact valid. If you wrote “I’m angry at you,” I had to believe that you were still in some sense angry, and you had to believe it, too, or else you came apart at your own seams. Emotions and states of mind persisted, which was healthy for us all, because the alternative is too entropic. Now updates can be issued hourly, or even more minutely than that, and these ongoing amendments to the self cannot help but erode or erase broader outlines. Now that individuals can announce that they are angry and immediately announce that they are no longer angry, what is anger, and what are individuals? This may be a second reason why people like my friend Roddy don’t make real-world announcements about their real-world relationships. Those things are more definite and less ephemeral than status updates. Deciding upon them requires more effort, as does changing them. Real pain may be involved, as well as real painkilling. The online world, by contrast, is a cyclical (non)painkiller: it cures loneliness by creating a more profound loneliness. And while it is easy to imagine a more complete or compelling account of this process, it is also easy to imagine a world that, moving forward, is hostile to patience, pacing, or psychological complexity. I have told people this and they have laughed at me. They have said “old young man” scornfully. We will see. All I can say for certain is that many of the struggles in my novel—and the real events in my life to which they correspond—would not make as much sense in a world where news about the self is commonly dispatched via Twitter: again, inside-out.

3.

I am concerned that the division between private and public has been imbalanced by online networks. I urge people to restore the balance.

3a.

When advising people on how to spend their time after delivering a massive, almost Stegosauran paragraph criticizing one of the modern world’s most common methods of spending time, it is customary to wrap up with a joke and get out quick. Here is a joke: “And the Lord saw that Adam was bored and sent Eve. And the Lord saw that Adam and Eve were bored and sent Twitter.” I saw that online somewhere. It may be true, in which case it is not only funny but sad. I forwarded it to my friend Roddy along with a note: “You should post this on your blog.” He replied to say that he was going out of town this weekend. There was no mention of his girlfriend, though I am sure she is accompanying him, and sure that she will show up in pictures on his Facebook page. He has not posted the joke to his blog yet, which is not funny but may not be sad.

New Yorker editor and novelist Ben Greenman is currently on a book tour for Please Step Back. (Previously.)

-

1

Pingback on May 18th, 2009 at 2:09 pm

[…] a comment » An interesting and entertaining editorial at Fictionaut’s blog by Ben Greenman, editor at The New Yorker and author of Correspondences […]

-

2

Pingback on Jun 1st, 2009 at 3:45 pm

[…] recently put up a variation on Stewart Brand’s theme from Ben Greenman, editor for The New […]

-

3

Pingback on Aug 17th, 2010 at 10:15 am

[…] Ben Greenman (”should vanish in a hail of fire before [it] poisons our species further“) to Judith Lawrence (”like throwing a gem into the ocean“), opinions on […]

May 18th, 2009 at 1:55 pm

I wholeheartedly agree with 1., 2., 2a., and 3. It would not make much sense for me to say that I agree with the other bits.

Another boon/problem is the exposure to many fine new books that comes from time spent in these social networks, and the lack of time to read those books. I’ve come across many a new author/book that I might not have heard about without Facebook, Twitter, my blog, Identity Theory, etc. – and most of them are currently piled up around the bed, annoying my wife and tripping me up in the middle of the night. I used to finish a book in a week or two – in junior high school, reading “Doctor Who” books, I was reading a book a day. If I was in junior high now, Facebook etc. would make this unlikely.

In summation: SN makes it possible for me to learn about and secure copies of many exciting books that I then do not have time to read.

May 19th, 2009 at 11:00 am

I love twitter but I know that is is wreeking havoc on my life. I knew the same about facebook before it and the same about myspace before that. I go deeper and deeper in, and I know that when I’m doing it, it’s a problem, but I can’t stop. does that mean it’s an addiction? I have even started to imagine what people are actually doing when I read their tweets. if a friend of mine tweets that she “went to mars bar and had a beer,” I imagine her there, drinking a beer. at this point I don’t go out of the house much, and even when I do, I’m connected to twitter and facebook with my iphone. does this mean it’s an addiction?

May 19th, 2009 at 12:42 pm

I will paraphrase Karl Popper on television:

We need an institute for people who use Twitter like the institutes for doctors. They become provisionally licensed then they take courses which draw their attention to the dangers to our civilisation. Then, on the basis of an examination, they take an oath that they will be always aware of these dangers and act accordingly and then they obtain the freedom to use Twitter. Or Facebook. Or the Internet in general.

May 19th, 2009 at 1:10 pm

I am Twittering this debate in pieces.

May 19th, 2009 at 5:54 pm

I read about a month ago that Twitter and Facebook create immorality. That seemed untrue. But this seems true.

May 19th, 2009 at 7:02 pm

Jim: I read that the first time through with “immortality” subbed for “immorality”. Maybe both?

May 19th, 2009 at 8:21 pm

I can’t help but cry when I think about the way this country has become obsessed with pointless information. Twitter is, for me, the epicenter of that process. I won’t tell you my age, but I am old enough to remember when people had to get up off of their rears to deal with other people. No texting, no twitters, no facebook. This internet is a big Pandora’s box.

May 22nd, 2009 at 11:38 am

I question your philosophy somewhat — I don’t know if individuals are breaking down the way you say — but I concede that it is philosophy, which pleases me. It’s nice to have an organized set of thoughts about the Hydra.

May 22nd, 2009 at 8:34 pm

This is absurd. Twitter is the best thing ever. How else would I know about such topics as magic, exercise, and xenophobia?

May 23rd, 2009 at 7:47 am

http://www.current.com/supernewsTwitter

Excellent video relating to this.

May 23rd, 2009 at 10:59 am

Hey — My mother is named Shabadooya. Is it a family name? Maybe we are related.

Sep 1st, 2009 at 2:45 pm

Karen, I can’t help but think it Ironic that you’re making that statement from the internet!